Don’t Invest in Paper Mills Just Because People Are Hoarding Toilet Paper

And other lessons on venture investing during a crisis

And other lessons on venture investing during a crisis

Even though toilet paper is out of stock, manufacturers are not increasing supply. Having been in the business for a long time, they know consumers hoard toilet paper in times of crisis — it’s happened before during Hurricane Katrina and the fallout from 9/11. They also know the scarcity is followed by an immediate decline in demand as consumers go through the extra rolls filling up their cabinet. Seeing the shortage, a reactive investor might rush to invest in paper mills. A more savvy investor knows not to. It boils down to a simple fact: The rate with which we go to the toilet has not fundamentally changed.

In times of crisis, basic business indicators can become extraordinary — almost unrecognizable. Grocery stores are reporting 80% week over week growth. Travel, hospitality, and real estate transactions have come to a standstill. Should venture capitalists back online grocery experiencing record growth or a travel startup that’s unlikely to have any meaningful revenue for the next quarter? The answer is nuanced.

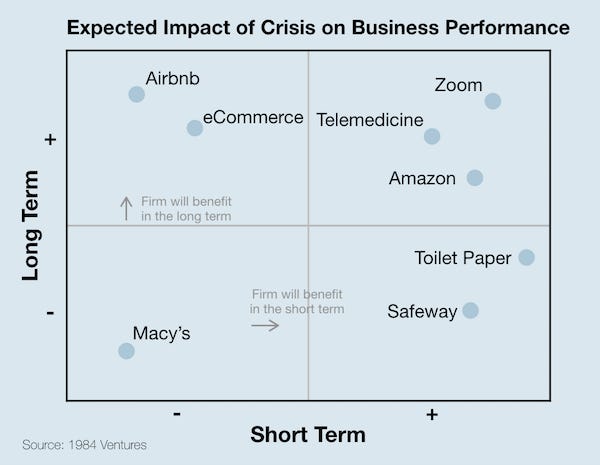

By plotting the long-term impact of the crisis against short-term impact, an interesting picture emerges. On the bottom left of this grid are industries suffering both in the short and the long term. Think Macy’s, already in decline and now forced to shut its doors for the foreseeable future. The crisis has likely accelerated an inevitable demise.

The top right quadrant is equally obvious. Zoom use is at an all-time high. E-commerce, video conferencing, and telemedicine all fall in this bucket: trends accelerated by the crisis. It’s a good place to already be an investor. But new investors must contend with frothy valuations.

The remaining two buckets are more nuanced. At the bottom right are industries that will benefit in the short term but will not be affected over the long term. Our toilet paper story is a prime example. Food supply, ventilators, and many health care products fall in that bucket. There may still be good opportunities for a public investor, but less so for venture investors. A few startups in these industries may see a short-term cash infusion; most won’t even launch till the glut is over.

The last quadrant, on the top left, is arguably the most interesting. The companies in this quadrant will suffer in the short term but will outperform the competition over the long term. A good example is Airbnb. While the business is facing a major drop in bookings, Airbnb’s asset-light model and the likely demise of many traditional hotels points to future dominance. Not surprisingly, while the CEO of Marriott issued a heart-wrenching plea to his employees, savvy venture investors went to Airbnb asking if it would raise capital.

If history is any guide, it’s the upper left quadrant that will likely see disproportionate venture returns. Google raised its financing just as the first tech bubble burst and investors were avoiding search companies like the plague. And Uber and Airbnb both were founded during the 2008 financial crisis when global travel was down 25%. At a time when cash is not readily available to most companies, investors may be tempted to only support these companies flush with revenue. But those with the stomach to focus on the long term will reap disproportionate rewards.